I know firsthand how confusing it can be for new drone pilots to figure out which uk drone laws apply to them in 2026. With regulations changing almost every year, it's a real challenge to keep up.

That's why I've created this guide: to answer your common questions in plain English about drone registration, where you can fly, licensing, upcoming 2026 changes, weight categories, drone remote ID, the CAA’s Drone Code, commercial use, insurance, and penalties.

30 Second Summary

- Before you fly, check if your drone requires a Flyer ID and Operator ID, as this is mandatory for all drones that have a camera and weigh 100g or more.

- You must always fly below 120m (400ft), keep the drone where you can see it, and stay at least 50m away from people.

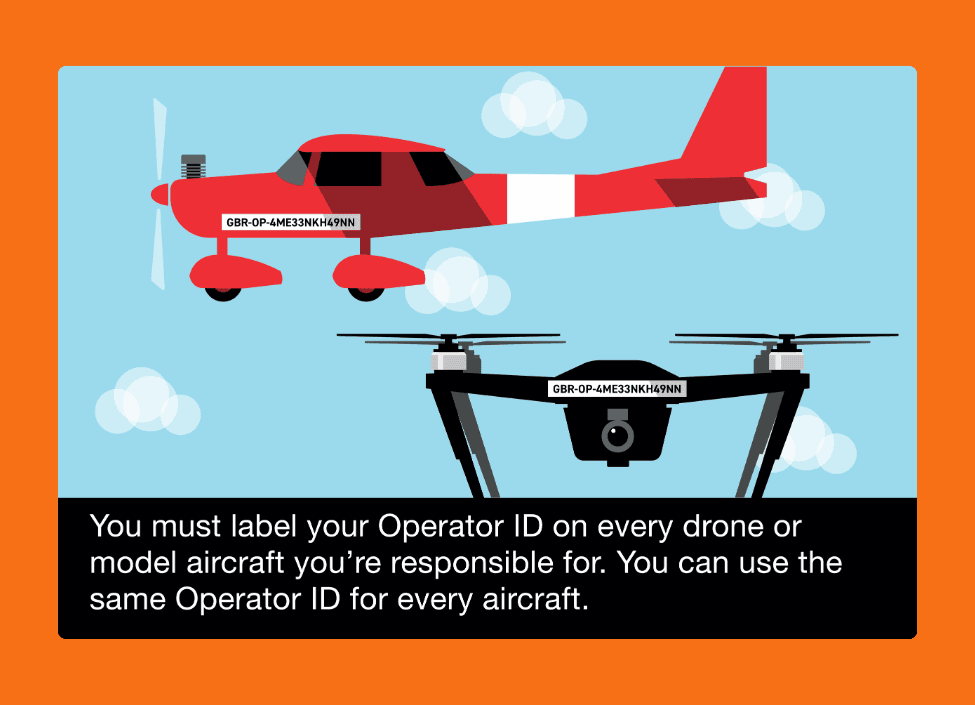

- You must physically label your drone with the Operator ID number you receive from the CAA.

- You must know your drone's weight, as the rules are much stricter for any drone over 250g.

- You must check a drone safety app (like NATS Drone Assist) for no-fly zones like airports before you take off.

Do I Need a License or to Register My Drone In UK?

In the UK, you don’t need a traditional drone pilot’s “license” for most drones, but you do need to register in almost all cases.

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) requires most drone flyers to pass an online theory test to get a Flyer ID and to register as a drone operator to get an Operator ID.

These two IDs are effectively your authorisation to fly:

Flyer ID: You obtain this by passing a free online test (it shows you know how to fly safely). It’s required for anyone flying drones above certain weights.

Operator ID: You get this by registering with the CAA (with a small annual fee). It indicates who is responsible for the drone. The operator is usually the owner or adult in charge.

It’s against the law to fly without the required IDs. Failing to register can lead to fines up to £1,000, and serious violations (like endangering aircraft) carry even harsher penalties (more on that later).

In short, yes – you likely need to register your drone before flying it outdoors in the UK.

What drones must be registered?

The requirement depends on your drone’s weight (and whether it has a camera):

Drones 250g up to 25kg: Registration is mandatory. You must have both a Flyer ID and an Operator ID for any drone in this weight range.

Drones 100g to 249g: If it has a camera, you need both IDs (Flyer ID and Operator ID) as well. If it’s camera-free and under 250g, a Flyer ID is still required, but getting an Operator ID is optional (though recommended). In practice, most drones in this class do have cameras, so you should register. This is the most common weight class for hobbyist drone pilots in uk, so if you own a popular model like the DJI Mini 4/5 Pro or DJI neo, these rules apply directly to you.

Drones under 100g: You do not have to register or take the test by law, but the CAA strongly recommends getting a Flyer ID regardless. It’s good for your knowledge and safety. Operator ID for sub-100g is optional.

Until 1 January 2026, the rules are slightly simpler: you must register (Flyer ID/Operator ID) if your drone weighs 250g or more, or if it’s under 250g but has a camera (and isn’t a toy).

After that date, as shown above, the threshold lowers to 100g for some requirements.

In summary, most drone owners in the UK will need to do the free test and register online before flying. It’s quick and easy – and it keeps you on the right side of the law.

How Do I Get a Drone Operator ID or Flyer ID?

Getting your Flyer ID and Operator ID is a straightforward online process through the CAA – here’s how it works:

Feature | Flyer ID | Operator ID |

|---|---|---|

Who Needs It? | Anyone who flies a drone 100g+ with a camera, or any drone 250g+. | Anyone who owns or is responsible for a drone 100g+ with a camera, or any drone 250g+. |

What Is It? | A certificate to prove you passed the safety test. | A registration number to be put on every drone you own. |

Cost | Free | £11.79 per year |

Renewal | Every 5 years (re-test) | Annually |

Flyer ID (the theory test)

To obtain a Flyer ID, you need to pass the CAA’s online drone theory test. You can access this on the CAA’s Register Drone and Model Aircraft portal.

The test is free.

It consists of multiple-choice questions (about 40 questions) covering the drone rules and safety practices – basically everything in the Drone Code. You can prepare by studying the Drone Code and perhaps taking some practice quizzes (the CAA provides study materials).

The pass mark is 75% (in other words, you need to get roughly 30 out of 40 questions right – though the exact passing criteria will be given on the test page).

The good news: you have unlimited attempts if you don’t pass the first time, and the questions aren’t meant to be tricky. They just ensure you know the important basics.

Once you pass, you’ll be issued a Flyer ID immediately. It’s an e-certificate (nothing physical is mailed).

The Flyer ID is valid for 5 years, after which you’ll need to re-take the test to refresh your knowledge. (If a child under 13 is flying, they still must pass the test, but a parent/guardian must administer it for them.)

Operator ID (drone registration)

To get an Operator ID, you register on the same CAA online portal (you can do it in the same session as the Flyer ID test – most people get both at once).

The person who registers as the Operator should be 18 or older (if you’re younger, a parent or another adult will have to register as the operator, even if you’re the one flying/owning the drone).

The registration form will ask for your contact details and some basic info. You’ll need to pay a small annual fee – currently about £11.79 per year for the Operator ID. Payment is online (credit/debit card).

Once done, you’ll receive your unique Operator ID number (something like “OPA1234-XYZ”).

This ID is valid for 12 months at a time, tied to the fee renewal.

Important: You must label every drone you own with your Operator ID in a visible place.

Typically, people stick a little label or write the ID on the drone’s body or inside the battery compartment (as long as it’s accessible without tools). This helps authorities trace the drone back to you if needed. One Operator ID covers all your drones – you don’t need separate IDs for each drone.

You Can Get your Flyer ID And Operator In Under 20 Mins

The CAA website will guide you step by step. Essentially it’s: create an account, take the Flyer ID test, register as an operator, pay, and you’re done. It usually takes less than 30 minutes.

Afterward, you’ll have a Flyer ID (usually an ID number or confirmation email, plus you can download a certificate) and an Operator ID number.

Carry proof of these when you go flying. You might show the email or certificate if asked by police or land authorities. (You don’t get a physical card by default, but you could print the certificate or order a card from third parties if desired.)

Renewals: Flyer ID renewal is every 5 years (re-test), Operator ID every 1 year (with fee). The CAA will send reminders when it’s time to renew. Keep your contact info up to date in the system.

What Is the CAA’s Drone Code?

The Drone and Model Aircraft Code (often just called the Drone Code) is basically the UK’s handbook of do’s and don’ts for flying drones safely and legally.

If you think of the driving world, it’s analogous to the Highway Code but for drones. It’s a distilled set of guidelines issued by the CAA, and if you follow them, you’ll be in compliance with the law for standard operations.

The Drone Code is built around key principles for safe flying. Many of them we’ve touched on in earlier sections, but let’s list the core points of the Drone Code clearly:

Always keep your drone in sight – and only fly it if weather conditions allow you to see it clearly (day or night with proper lighting).

Stay below 120m (400ft) altitude at all times.

Maintain safe distances from people and property: Generally at least 50m from people and properties, and 150m from residential or built-up areas if your drone is larger. Never fly over crowds.

Never fly near airports or aircraft: Check for any airport Flight Restriction Zones and stay well clear without permission. Drone flights near airports can be catastrophic – you could end up jailed for endangering aircraft.

No flying in restricted areas or sensitive locations: This includes near prisons, military ranges, nuclear power stations, etc., or temporary no-fly zones (NOTAMs) for events. Use the drone safety map or apps to identify these.

Don’t fly in emergency response areas: If there’s an accident site, fire, or police operation, keep your drone away so you don’t interfere.

Be fit to fly: That means no alcohol or drugs that could impair you while operating a drone. Also, be rested and attentive – you are the drone pilot in command.

Respect privacy: You should avoid flying over private homes or gardens without permission. The Drone Code explicitly reminds you to respect other people’s privacy and data – don’t be that “peeping drone” person. (This can have legal consequences under harassment or data protection laws if you violate privacy.)

Check your drone before flight: Ensure the battery is charged, the drone is in good condition, and you’ve done all pre-flight safety checks (compass calibrated, etc.). While not always stated explicitly in the summary, it’s part of flying safely.

Understand which category/rules apply to your drone: As noted, sub-250g drones have slightly different allowances than larger ones. The Drone Code expects you to know which category (A1, A2, A3) you’re flying in and obey those specific limits. If you plan to operate outside the Code’s standard rules (e.g., closer than 50m to people, beyond line of sight, etc.), you must obtain the proper authorisation first.

Essentially, the Drone Code is common-sense guidelines codified into rules. It’s available on the CAA website and is a must-read for new drone pilots. In fact, you’ll need to know its content to pass your Flyer ID test.

By following the Drone Code, you ensure you’re flying safely, legally, and responsibly. The CAA’s mantra is “safe flying, good flying” – if you always keep safety and respect in mind (for others in the air and on the ground), you’ll be on the right track.

From January 1, 2026, Remote ID will become a mandatory legal requirement for many drones operating in the UK. This system is designed to enhance airspace safety and security by allowing authorities to identify drones during flight.

What is Remote ID?

Remote ID, often called RID, is a system that enables a drone to broadcast identification and location information while it is in the air. The purpose is to allow law enforcement, aviation authorities, and other parties to distinguish between legally operated drones and those that may be flying irresponsibly or illegally.

The UK is initially implementing a system called Direct Remote ID (DRID). This technology broadcasts information directly from the drone using common wireless signals like Wi-Fi or Bluetooth, which can then be received by nearby devices such as smartphones without needing an internet connection.

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) views this as an interim solution, with a longer-term goal of adopting a Hybrid RID system that combines local broadcasting with internet-based network transmission for more comprehensive tracking.

Phased Implementation Schedule

The requirement to use Remote ID will be rolled out in two main phases:

Phase 1: From January 1, 2026

- 1

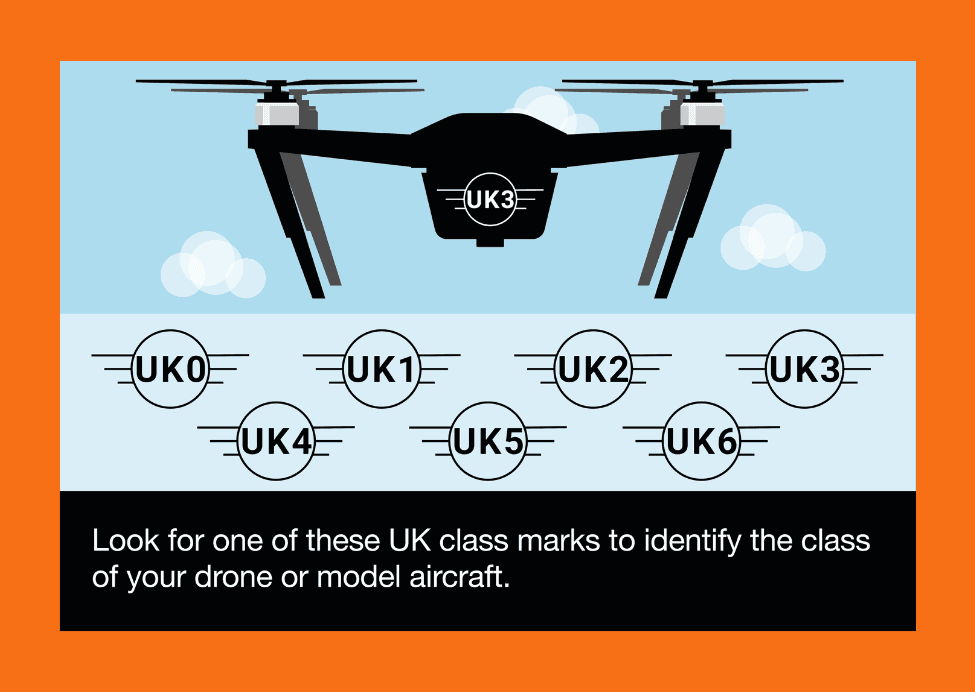

Remote ID becomes mandatory for all newly manufactured drones with specific UK class marks: UK1, UK2, UK3, UK5, and UK6. These drones must have Remote ID functionality built-in by the manufacturer, and the pilot must have it active during flight.

Phase 2: From January 1, 2028

After a two-year transitional period, the requirement extends to a wider range of aircraft.

Remote ID will be mandatory for legacy drones (those without a UK class mark), privately built drones, and UK0 class drones that weigh 100g or more and are fitted with a camera.

The information broadcast will be linked to the drone's operator registration, ensuring traceability for authorities.

How to Comply with Remote ID

New Drones: For drones purchased from 2026 onwards in the relevant UK classes, Remote ID will be a built-in feature that must be enabled.

Legacy Drones: Owners of older drones (without a class mark) that fall under the 2028 rules will need to retrofit their aircraft with an add-on Remote ID module. It is important to note that the weight of this module will be added to the drone's total take-off mass, which could potentially move the aircraft into a higher weight category and subject it to different operational rules.

Exemptions from Remote ID requirements may be granted for flights within the confines of recognized flying clubs or under specific Operational Authorisations from the CAA. Flights conducted indoors are also exempt.

Where Am I Allowed to Fly My Drone?

You can’t just fly your drone anywhere you want. There are clear UK drone laws on where and how high you can fly to keep everyone safe.

Maximum Altitude – 120m (400ft): You must not fly above 120 meters (about 400 feet) from ground level. This helps avoid conflict with manned aircraft, which generally fly higher. Always be alert for low-flying aircraft like police or air ambulance helicopters.

Maintain Line of Sight: You should always be able to see your drone with your own eyes (not just via a video feed) at all times. Don’t fly into clouds, fog, or too far away to see – it’s illegal to fly Beyond Visual Line of Sight without special permission.

Stay 50m Away from People: By default, keep at least a 50-meter horizontal distance between your drone and any people not involved in the flight. Think of a cylinder extending 50m around and above people – you shouldn’t enter that cylinder with your drone. Do not fly directly over people who aren’t with you. (There is an exception for very small drones – see the next section on weight categories – but 50m is a good general rule.)

Never Fly Over Crowds: You must not fly over assemblies of people at any height. A “crowd” means people packed together who can’t quickly move away – for example, concerts, sporting events, busy beaches, rallies, etc. Even a tiny drone could cause panic or injury in a crowd, so it’s strictly forbidden.

Distance from Buildings (if heavier drone): If you’re flying a larger drone in the Open Category A3 “far from people”, keep at least 150m away from residential, commercial, industrial or recreational areas. Essentially, “built-up areas” are off-limits for big drones unless you have special approval. However, lightweight drones under 250g are allowed to fly in residential and urban areas (more on this in the weight section). Always check what category your operation falls into.

Stay Away from Airports and Restricted Airspace: It is illegal and extremely dangerous to fly near airports, airfields, spaceports or aircraft in flight. Major airports have Flight Restriction Zones (typically several kilometers around and above the airport) – never fly in these zones without explicit permission.

If you endanger an aircraft, you could face up to 5 years in prison.

Use tools like the NATS Drone Assist app or online maps to identify no-fly zones and airspace restrictions before you fly. Other no-fly areas include near prisons, military bases, and certain government or infrastructure sites, as well as temporary restrictions for events or emergencies.

Avoid Emergency Situations: Do not fly near firefighting operations, accident scenes, or other emergencies. If an emergency happens near you while you’re flying, safely land immediately – drones must not interfere with emergency responders.

Respect Privacy and Property: While not an airspace rule, remember you shouldn’t snoop on people with your drone. Don’t hover over someone’s house or garden without permission – this could breach privacy laws. Always be considerate and obey any local council or park bylaws that ban drone flights in certain areas.

In UK law, you must not fly closer than 50m horizontally to people, and you should never fly directly over them. Small drones under 250g have more flexible rules, but you still must not endanger anyone.

In practice, a good pre-flight checklist is: check your surroundings and airspace on a drone app, keep below 120m, stay well clear of people and buildings unless your drone and certification allow it, and avoid sensitive areas. If you follow the Drone Code (height, distance, no crowds, no airports, line-of-sight), you’ll be flying within the law.

When in doubt, don’t fly there. Find a safer location or get the proper authorization for more advanced operations.

What Do the Different Drone Weight Categories Mean?

You’ve probably noticed a lot of weight classes mentioned (100g, 250g, 900g, 2kg, 25kg, etc.).

Weight is a fundamental factor in drone law. Lighter drones are considered lower-risk, so they have fewer restrictions, whereas heavier drones are more tightly regulated.

Here’s a breakdown of what the key weight categories mean for you as a drone pilot:

Drone Weight Category | Flyer ID Needed? | Operator ID Needed? | Can I fly near people? | Common Drones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Under 250g | Yes (if has camera) | Yes (if has camera) | Yes, but not over crowds. | DJI Mini Series, DJI Avata |

250g - 500g | Yes | Yes | No, must stay 50m away. | DJI Air Series |

500g - 2kg | Yes | Yes | No, must stay 50m away (unless you have A2 CofC). | Yuneec Typhoon |

2kg - 25kg | Yes | Yes | No, must stay 150m from built-up areas. | DJI Matrice Series |

Drones under 250g (DJI Mini’s, DJI Neo)

This is a major threshold. Drones weighing 249 grams or less (like the DJI Mini series) enjoy the most freedom.

Why? Because a lightweight drone carries much less kinetic energy, meaning it’s far less likely to cause serious injury or damage.

If you have a sub-250g drone, you can fly closer to people than larger drones are allowed. In fact, you’s allowed to fly over people incidentally (just not over crowds) with these little drones. You can also fly them in residential and urban areas without the 150m distance restriction that bigger drones have.

Importantly, the smallest drones might not even require registration if they have no camera (though in practice almost all do have cameras now).

Bottom line: sub-250g drones are the easiest to fly legally – perfect for beginners and casual users because many rules (like the 50m and 150m distance rules) don’t apply as strictly.

Just remember, “under 250g” doesn’t make you immune to all rules – you still must not endanger people or fly recklessly.

Drones 250g to 500g (DJI Avata)

This is a bit of a niche sub-category (often called “A1 Transitional” under older rules). If you have a drone in this weight range, current transitional rules (before 2026) allowed some privileges with an A2 CofC, but broadly speaking you have more restrictions than the sub-250g class.

Without a class mark, a >250g drone cannot fly over uninvolved people at all and must stay 50m away.

In general, once you cross 250g, the rules get stricter: registration becomes mandatory, and you start falling into either A2 or A3 subcategory depending on scenario. Many popular camera drones (DJI Mavic Air, etc.) weigh in this 250-500g bracket, and while they’re still quite portable, you need to be mindful of distances from people unless you have a cert that allows closer operations.

After 2026, a drone in this range would likely need a class C1 marking to have more freedom; otherwise it will be treated as legacy.

Drones ~500g to 2kg (Yuneec)

I group these together because 500g and 2kg were important cut-offs in the transitional rules. A drone heavier than 500g (but under 2kg) traditionally required an A2 Certificate of Competency (A2 CofC) to fly in built-up areas with reduced distance. Otherwise, you’d be pushed to A3 (meaning you have to be in a wide open space, 150m away from residential areas and no people around).

If your drone is in this class and you do not have any special certificate, you essentially must treat it as A3: keep well away from people (no uninvolved people in 50m) and away from any congested area. With an A2 CofC, you could reduce the distance to 50m in A2 category until the transitional provisions expire.

The exact numbers aside, the concept is: once drones get larger and heavier (approaching a couple of kilograms), the law expects you to either keep them far from people or invest in further training/certification to mitigate the risk.

Drones 2kg to 25kg (DJI Matrice 300)

25kg (which is about 55 lbs) is the upper limit of what’s considered a “small unmanned aircraft” for the Open and Specific categories.

If your drone is in the 2–25kg range, by default you’re definitely in the A3 subcategory for recreational use (far from people, 150m from any built-up area) unless you have an Operational Authorisation from the CAA to do something else. Drones in this weight class are usually industrial or large custom rigs.

All drones in this range require registration (Flyer ID & Operator ID) by law.

Flying a 10kg drone, for instance, in a park near people would never be allowed under the basic rules. You’d need to be in a controlled environment or have special permissions. So, practically, if you’re a new hobbyist you probably aren’t dealing with such a heavy drone. But if you are, know that you’re in the realm of strict regulation.

Drones above 25kg

These are not allowed in the Open category at all.

Operating drones larger than 25kg requires special certification, airworthiness approvals, and usually falls under the Certified Category (which is akin to how manned aircraft are regulated). This is well beyond the scope of hobby or even most professional drone work.

Also, note that any drone over 20kg (even if somehow flying recreationally) legally requires insurance and specific permission to fly. In short, >25kg is basically drone territory that is treated like an aircraft.

In summary, weight matters a lot. The 250g mark is where registration and most safety distances kick in. The 500g and 2kg marks were part of older transitional allowances (tied to A2 CofC usage) – showing that as weight increases, operations get restricted without further pilot competency. And 25kg is the absolute ceiling for standard drone operations in the “simpler” categories.

Always check which category your drone falls into and what that means for your flying.

When in doubt, lighter is safer (and legally simpler) – that’s why sub-250g drones are so popular, as they let you do more with fewer rules.

What Are the New Drone Class Marks (Coming in 2026)?

Big changes are on the horizon! The UK is introducing a drone class marking system in January 2026.

This system is similar to what the EU has already implemented, and it will assign drones a “class” (UK0, UK1, UK2, UK3, UK4, UK5, or UK6) based on their weight and capabilities. Think of it like an official rating label for drones – each class mark indicates what safety standards the drone meets and in which scenarios it can be used.

Starting 1 January 2026, any new drone model released on the UK market must have a class mark label (UK0 through UK6). For example, a tiny toy drone might be class UK0, while a larger drone with more safety features could be class UK1 or UK2, etc.

These labels will cover requirements like the drone’s weight, built-in safety features (e.g. does it have a low-speed mode or geo-fencing), and tech like remote ID transponders. The class tells you which subcategory of operation the drone is allowed in. For instance, UK class 0 or 1 drones can be flown in the A1 (over people) category, UK2 is for A2 (near people) use, UK3 and UK4 for A3 (far from people) use, and so on.

So, why is this being done?

Essentially to align with international standards and make it clearer what rules each drone must follow.

Until now, the UK has been using weight-based rules and “transitional” provisions for older drones. The class marking will bring more nuance: manufacturers will build drones to meet certain safety criteria and get them class-certified.

As a drone pilot, if you buy a class-marked drone, you’ll immediately know what operations you can do. For example, a drone marked “C1” (or UK1) will be under 900g and safe enough to fly over people (with some caution). A “C2” (UK2) drone (under 4kg with more safety tech) is intended for closer-to-people operations (A2 category) but not over them.

Higher classes like C5 or C6 (UK5/UK6) are for advanced operations (e.g., drones with heavy payloads or specific tasks, likely in the Specific category).

Starting in 2026, new drones will feature these class identification labels. The class indicates the drone’s weight and safety standard, which in turn determines what rules apply – e.g. UK0/C0 for drones <250g, UK1/C1 for drones <900g with certain features, UK2/C2 for drones <4kg, etc. If your drone has a European “C” mark, it’s recognized as the equivalent UK class until end of 2027.

Transitional period: What if you already own a drone today that has no class mark?

Don’t worry – you can still fly it. All drones sold before 2026 are considered “legacy” drones.

The UK has a transitional provision in place up to Jan 1, 2026, which allowed older drones to be used under somewhat relaxed rules. Once class marks kick in, those older drones without a class will generally be treated as A3 category only (meaning you’ll have to fly them far from people and away from urban areas, unless they’re very light).

For instance, currently a <500g legacy drone can be flown under A1 transitional rules, but after 2026 that ends. That drone will likely be restricted to A3 (or you’d need to get an Operational Authorisation to fly it in busy areas).

The good news: if your drone has a EU “C” class marking on it (some newer European models do), the UK will recognize that as equivalent to a UK class for a few years. In fact, until 31 Dec 2027 you can operate a drone with a EU C0-C4 marking as if it’s UK class 0-4 respectively. So you won’t be penalized if you bought a drone abroad that has a CE class label; it maps over (at least during that transition period).

In summary, 2026’s class marks are about making drone regulations more device-specific. As a new drone pilot, you should be aware that in the near future drones will be sold with labels like “UK1” or “C2” which tell you what rules you can fly under.

And if you keep using your older drone, just check the latest CAA guidance – you might face more restrictions on it after the transition period ends (especially if it’s heavier).

The aim is to improve safety by ensuring new drones meet higher standards and giving drone pilots more flexibility if their drone is certified safe.

What Are the Different Drone Licences and Qualifications?

The terminology can be confusing, because people talk about “drone licences.” In the UK, there isn’t a single blanket “drone licence” you carry. Instead, there are a few certificates/IDs and qualifications depending on what you want to do:

Starting in 2026, the UK is introducing significant updates to its drone regulations, including a new licensing structure known as the Remote Pilot Competency (RPC) framework. This tiered system is designed to align a pilot's qualifications with the complexity and risk of their drone operations.

The Remote Pilot Competency (RPC) Framework

The RPC framework is a progressive qualification system for drone pilots conducting operations within the 'Specific Category'. It became mandatory for any pilot operating under the UK Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) framework as of April 23, 2025, which replaced the previous Operating Safety Case (OSC) process.

The core purpose of the RPC is to ensure that pilots have the proven skills and competency required for the specific risk level of their flight, particularly for more complex operations that go beyond the basic 'Open Category' rules.

The Four Levels of RPC

The framework is structured into four levels, each corresponding to an operation's Air Risk Class (ARC) and authorising increasingly complex flights.

RPC-L1 (Visual Line of Sight - VLOS): This is the foundational certificate, covering operations where the pilot keeps the drone within their direct line of sight at all times.

RPC-L2 (Intermediate BVLOS): This intermediate license is the entry point for Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations. It permits flights in controlled, low-risk, and segregated airspace, known as Air Risk Class A (ARC-a). To qualify for an RPC-L2, a pilot must be at least 18, already hold an RPC-L1, and have logged a minimum of 50 flight hours.

RPC-L3 & RPC-L4 (Advanced BVLOS): These advanced certificates are for pilots conducting high-risk BVLOS missions in more complex airspace environments.

To obtain these qualifications, pilots must typically pass theory exams, undergo practical flight assessments, and meet a minimum requirement for logged flight hours. The RPC-L2 license, for instance, is valid for three years and requires pilots to log at least two hours of flight time every 90 days to maintain their currency.

What This Means for Drone Pilots

The introduction of the RPC framework has several key implications for drone pilots in the UK:

Structured Career Progression: The tiered system provides a clear pathway for pilots who wish to advance from simple VLOS flights to more complex and potentially more lucrative BVLOS operations.

Mandatory for Specific Category: For any commercial or complex flight that falls into the Specific Category under SORA, holding the appropriate RPC level is a legal requirement. You cannot fly a mission that has a higher Air Risk Class than your qualification allows.

Enhanced Safety and Compliance: By directly linking a pilot's competency to the mission's risk level, the framework aims to ensure safer and more compliant drone operations across the UK.

A2 Certificate of Competency (A2 CofC)

This is an additional voluntary qualification you can obtain if you want to fly in the “A2 (Near People)” subcategory of the Open Category.

The A2 CofC involves a bit of training (often an online course + exam through a CAA-recognized training provider). Why get an A2 CofC? It allows you to fly certain drones (usually <2kg) closer to people than normally allowed in A3.

For example, with an A2 Certificate of Competency (A2 CofC) you can operate a 1kg drone in a built-up area with just a 50m distance from uninvolved people, instead of keeping 150m away. In short, A2 CofC lets you do more “close proximity” operations with medium-sized drones.

It’s very useful for commercial work like roof inspections or wedding photography where you can’t stay 150m away from everything. (Note: after 2026, you’ll also need a class-marked drone of class C2 for A2 category – see the 2026 section.)

GVC (General Visual Line of Sight Certificate)

This is a more advanced certification intended for the Specific Category of operations (higher risk or outside normal rules).

Getting a GVC involves ground school training, an exam, and a flight skills assessment, usually with a CAA-approved entity. If you obtain a General Visual Line of Sight Certificate, you can then apply to the CAA for an Operational Authorisation.

An Operational Authorisation is what replaced the old “PfCO” (Permission for Commercial Operations) after 2020. Essentially, if you need to fly in ways not allowed under the basic Drone Code (e.g. closer than 50m to people, at night beyond line of sight, heavier drones over people, etc.), you’d be in the Specific Category and would need a GVC + Operational Authorisation from the CAA.

This is typically used by professional drone operators for complex jobs.

No Separate “Commercial Licence”

Under current rules, there is no longer a distinction between hobbyist and commercial flights in terms of licensing.

You don’t automatically need a “commercial drone licence” just because you’re getting paid. As long as you follow the rules of the Open Category (or have an Operational Authorisation for Specific Category), you can fly commercially without additional permission.

The focus is on how and where you fly, not whether you earn money. The old PfCO was discontinued at the end of 2020. Now, for commercial work, you simply ensure you’re in the correct category. Many jobs can be done under Open category rules (especially with an A2 CofC), and if not, you go for Specific category (GVC/OA).

In summary, the “licences” in the UK drone world are mainly the Flyer ID (basic legal requirement), and optional certificates like A2 CofC and GVC for advanced operations.

The one you need depends entirely on what kind of flying you plan to do. A recreational flyer with a small drone just needs the Flyer and Operator IDs, whereas a professional surveyor with a heavy drone might need the GVC and a CAA authorization. There are also a few other niche qualifications (like BVLOS ratings, FPV exemptions, etc.), but the above are the main ones for most drone pilots.

What Are the Rules for Commercial Drone Use?

One of the most common questions is: what if I want to use my drone for business or make money – are the rules different?

The short answer is the flight rules (where/how you can fly) are the same as for hobbyists, but there are a couple of extra obligations for commercial use.

No distinction in basic flight rules

Since 2021, the UK regulations no longer distinguish “commercial” versus “recreational” in terms of permissions needed to fly. You do not need a specific “commercial licence” or PfCO (that old permission was removed in 2020) just to do paid work.

If you can legally fly under the Open Category rules for a given scenario, you can do so whether or not it’s for profit. For example, if you have a sub-250g drone and follow the Drone Code, you can take photos and sell them without needing special permission.

Similarly, if you obtained an A2 CofC to fly a 1kg drone in a town for fun, that same certificate allows you to do it for work too – there’s no difference.

However, commercial operations often have greater demands, which might push you into needing additional certification or authorisation:

If your work requires flying in riskier situations than the basic rules allow (e.g., filming over an event crowd, or using a heavy drone in a built-up area), then you enter the Specific Category and need an Operational Authorisation from the CAA. This in turn means you’d likely need a GVC qualification and to submit a safety case (or follow a standard scenario) to get approval. Essentially, complex commercial jobs may require what we discussed earlier: the GVC and a CAA permission tailored to the operation.

For many standard commercial jobs – say real estate photography with a 700g drone – operators use the A2 CofC. With an A2 CofC and an appropriate drone (class C2 or legacy <2kg), you can operate in many populated environments legally (with some distance restrictions). This covers a lot of “commercial” work needs without going to Specific Category.

Do I Need Insurance to Fly My Drone?

Insurance is not always legally required for drone flying, but it’s an important consideration. Let’s break it down:

Recreational use (hobby flying)

If you are flying purely for fun, sport, or as a hobby, the law does not mandate that you have insurance (assuming your drone is under 20kg, which covers basically all hobby drones).

So, a kid flying a drone in a park or you taking landscape photos on the weekend doesn’t have to insure the activity by law.

However, you should seriously consider getting liability insurance even for hobby flying. Accidents happen – your drone could crash into a car or injure someone, and you’d be responsible.

Several organizations (like BMFA, FPV UK, or commercial insurers) offer inexpensive hobby drone insurance or it may be included with membership to a model aircraft club. It’s a small price for peace of mind because if something goes wrong, claims can be costly.

Many home insurance policies no longer cover drone incidents, so don’t assume your homeowner’s liability will help – often it won’t. In short, hobbyists: not required by law, but highly recommended to have 3rd-party liability cover.

Commercial or paid use

If you’re flying for any purpose other than recreation, UK law requires you to have at least third-party liability insurance for your drone operations.

This means if you use your drone for work (e.g. aerial photography business, inspections, etc.), or even in a volunteer capacity, you need proper insurance that meets the standards (EC785/2004 compliant, which basically sets minimum coverage amounts). The insurance should cover injury to others and damage to property caused by your drone.

Typically, commercial drone insurance also covers equipment damage, but that’s optional – liability towards others is the mandatory part.

Insurance is usually checked when you apply for any CAA permissions, and you might have to produce a valid insurance certificate if inspected during operations. Operating commercially without insurance can void your CAA authorisation and lead to penalties.

Drones over 20kg: If somehow you have a drone weighing more than 20kg (which would be unusual for hobby, more so for large industrial drones), insurance is required even for non-commercial use. But for 99.9% of typical users with sub-20kg drones, this clause is not encountered outside the commercial context.

Beyond legal requirements, consider what insurance provides. If your drone crashes, liability insurance covers the damage you caused, and hull insurance can cover the drone itself. Also, some insurance covers flyaways, theft, etc.

For hobbyists, companies like Coverdrone or FPV UK’s membership offer affordable packages. For professionals, there are comprehensive annual policies or on-demand insurance per flight.

Recap: Do you need insurance? If you’re a hobby flyer with a small drone: legally no, but it’s wise to have. If you’re a commercial flyer or doing anything non-recreational: yes, it’s legally required to have liability insurance.

Always check the latest CAA guidance and insurance regulations, but err on the side of caution. The skies are fun, but they come with responsibility – insurance is part of being a responsible drone pilot.

What Are the Penalties for Breaking UK’s Drone Laws?

The UK takes drone violations seriously. If you break the drone laws, you can face severe penalties – including fines, drone confiscation, and even imprisonment in extreme cases.

Here are some examples of what could happen if you don’t follow the rules:

Fines: Many drone-related offences carry fines on summary conviction. A common figure quoted is up to a £1,000 fine for things like failing to register (no Operator ID) or not having the required Flyer ID when flying. Indeed, if you’re caught flying without the necessary CAA registration, you could be fined £1,000 on the spot. Lesser infringements (like minor breaches of the Drone Code that endanger others) can also result in fines, which might vary depending on the offence and are determined by the courts. For more serious offences (see below), fines can be much higher.

Drone Confiscation: Law enforcement has the power to confiscate your drone if you’ve been flying it illegally. For instance, if you were flying in a prohibited area (say, next to an airport runway) or in a dangerously irresponsible manner, the police can seize your drone as evidence and to prevent further risk. Getting it back might be a long process (and not guaranteed, especially if used as part of the punishment or if the court orders its destruction).

Criminal Charges & Prison: Some actions are considered criminal offences under the Air Navigation Order 2016.

The most serious is endangering the safety of an aircraft – if your drone is flown in a way that could hit an airplane or helicopter, you are committing a crime that can lead to up to 5 years in prison upon conviction.

Even if no accident occurred, the sheer risk you imposed can be enough for prosecution. Another example: flying in restricted areas like near airports without permission can lead to arrest and criminal charges.

Also, if you consistently flout privacy laws or use a drone for harassment, you could face charges under other laws (Harassment Act, etc.). The CAA and police have prosecuted drone pilots for reckless flying – for example, someone who flew a drone over a football stadium or a busy city street could be taken to court and potentially given a criminal record.

Fixed Penalty Notices: In some cases, the police might issue on-the-spot fines or notices for minor drone offences (this was introduced to give an alternative to full prosecution for less severe breaches). This could be a fine (perhaps £100-£200) for something like flying above 400ft or within a restricted area without causing actual harm – these frameworks are still developing under the Drone Bill/Act, but be aware that enforcement can happen in the field.

Civil Liability: Aside from criminal penalties, if your drone causes injury or property damage, you could be sued civilly. This is why insurance is important. For example, if your drone crashes through someone’s window or causes a car accident, you may have to pay for damages. For commercial operators, not having required insurance is itself an offence, but also leaves you on the hook personally for any harm caused.

Always fly responsibly. If you make a mistake, land immediately and learn from it.

The CAA tends to favor educating drone pilots for first-time minor breaches (you might get a warning), but they and the police won’t hesitate to punish willful or dangerous violations. By following the guidelines in this guide, you should never have to worry about penalties – you’ll be on the right side of the law.

Need Lawful Drone Services? Contact HireDronePilot

Navigating UK drone laws requires diligence—from securing your Flyer and Operator IDs to mastering the Drone Code and understanding the operational limits of your specific aircraft.

We perform drone roof surveys, drone lidar mapping and drone surveying for businesses across the uk. This is precisely the challenge HireDronePilot was built to solve.

Our network is exclusively for drone pilots with advanced qualifications like the A2 CofC and GVC, ensuring every operator you connect with is an expert in UK aviation law and complex flight operations. As the UK's premier managed marketplace, HireDronePilot connects businesses with verified professional drone pilots for hire.

We streamline drone services through competitive bidding, ensuring quality, compliance, and value for every aerial project across the United Kingdom.

To learn more, visit us at HireDronePilot.

Ready to execute your project with a fully vetted, insured, and certified professional? Find your expert drone pilot today and fly with confidence.

About the Author

Written by

Peter Leslie

Peter Leslie is a CAA-approved commercial drone pilot with 10+ years experience and over 10,000 flight hours. He holds the GVC and A2 CofC drone licences with full CAA Operational Authorisation. Peter is a member of ARPAS-UK, the UK's non-profit trade association for the drone industry. He founded HireDronePilot to connect UK businesses with qualified, insured drone operators.

Looking for More Drone Work?

Join the UK's leading network of professional drone pilots and grow your business.

Open Access

Bid on any job - all jobs open to all pilots

Grow Revenue

Access high-value commercial projects

Stay Busy

Fill your schedule with regular work

Related Articles

Our Drone Survey Service In Stirling, Scotland

Bringing you Stirling drone survey data from areas no one else can fly.

How Much Does A Drone LiDAR Survey Cost

Forecasting your drone LiDAR survey cost requires understanding what's hidden beyond the initial quote.

Step By Step Process Of Drone LiDAR Survey

Next, discover the crucial post-flight steps that determine your survey's success.